Future Scenarios

The intersection of AI and Climate Action in Asia is uncertain and complex. New approaches are needed to anticipate possible opportunities and challenges and better prepare for change. Foresight methods provide a structured way to anticipate future trends, engage stakeholders, and identify anticipatory strategies.

The expert network, along with additional participants from India, met for a scenario-building workshop in New Delhi in August 2023. A scenario is a story illustrating possible future worlds, or aspects of it. It is an exploratory tool to support decision-making, not a prediction of the future.

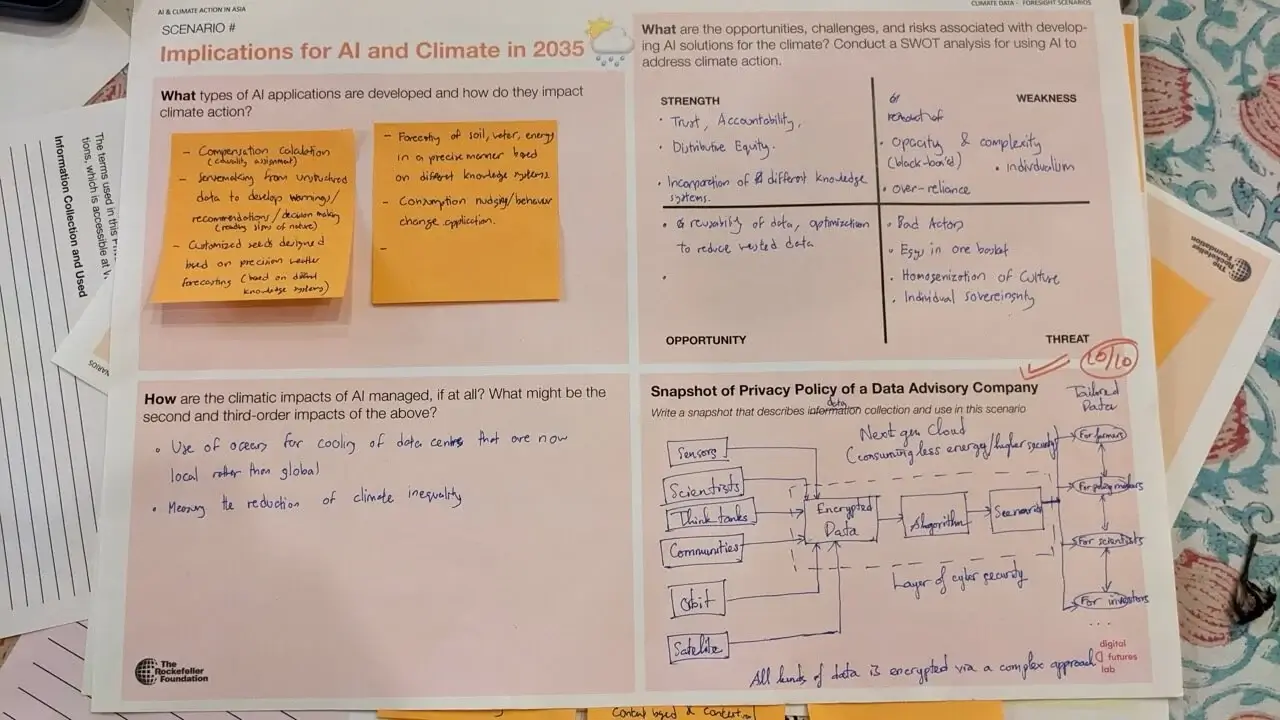

We explored hypothetical futures about two issues: Climate Data Governance and AI and Agriculture in Asia. We first identified critical but uncertain drivers of change relating to each of these issues. We then examined the interaction between these drivers and the possible outcomes for climate action in the region. To introduce the workshop methodology to the participants, we curated a pre-workshop guide, which can be read here.

Future of Climate Data Pipelines and Governance in Asia

- How might climate data pipelines and governance evolve over the next ten years?

- What are the likely implications for the intersection of AI and climate action in Asia?

Scenario 1: Fractured Futures

The increasing severity of the climate crisis has propelled a new supranational agency to collect and curate climate data. However, data quality is poor, and low-resource geographies and communities remain under-represented.

Some of the data sets housed by this new institution are freely available, but most need to be purchased. The sale of climate-relevant data sets is a critical source of revenue and sustainability for the new agency, but this has also led to a competitive market for climate data.

Concerned about the impact of climate change on their business interests, companies have formed private data clubs to host high-quality satellite data. Private companies own most high-quality satellites, while the government-operated ones are outdated and have fallen into disuse.

Companies use this data to develop disaster prediction tools based on multi-modal data to ensure their businesses and supply chains are protected against climate variability. AI is used to advance R&D on environmentally friendly materials and processes, which reduce private companies' environmental footprint. However, these technological advancements are unaffordable for smaller and informal businesses in the region.

Few AI-based interventions focus on the adaptation needs of communities most impacted by climate change. Governments encouraged private-sector pilots and market-based solutions to address climate action, but the lack of a viable business model led many companies to lose interest. Philanthropic investments were made, but without ownership by local governments, they were not sustainable.

The climate crisis is worsening in Asia. While mitigation measures by companies have improved, the impact on the climate crisis is marginal, particularly as the use of AI simultaneously also contributes to increased consumption and production.

Scenario 2: Hopeful Tomorrows

A climate-induced pandemic and the following economic and social disruptions forced governments to adopt a new course of action. Indigenous knowledge systems were prioritised in the new action plan, and rights were assigned to non-human forms of life.

Companies were required to develop a roadmap based on this action plan, and high taxes on fossil fuel use made it increasingly difficult for companies to remain profitable. The stringency of these mandates led to a new wave of technological innovation. Early wins from this new approach to climate innovation contributed to greater trust across countries and communities.

Governments, industry and communities are much more willing to share climate data and new data licenses based on principles of collective responsibility, reciprocity, and accountability are developed. Different actors have varying levels of access and usage rights to the data, contingent on the intended use of the data.

Data licensing, including monitoring compliance, is managed by a new supranational climate data agency. It uses AI-based tools to test the efficacy of the proposed solutions across multiple parameters, prioritising the protection of vulnerable populations and biodiversity.

Many local, community-managed innovation centres have been set up across the region to support decentralised solutions based on advances in no-code and edge computing. Bottom-up data collection and curation have also helped build 'digital twins' of vulnerable areas, helping policymakers and communities better plan and anticipate disasters.

Strong regulation propels technological innovation for climate mitigation and helps manage the risks of climate change. The elevation of traditional knowledge systems helps advance more sustainable and equitable climate adaptation and resilience strategies.

These two scenarios on the future of climate data pipelines and governance in Asia reflect a set of shared concerns voiced by the expert network and potential levers of change.

- Commercialisation of climate data

- Persistence of the Digital Divide

- Increasing dependence on private actors

- Lack of evidence around AI use for climate

- Misaligned political priorities

Shared Concerns

- Political will and public policy

- Societal trust and solidarity

- Community-centred data curation

- Preservation of local knowledge systems

- Equitable data-sharing mechanisms

Levers of Change

Future of AI and Agriculture in Asia

- How might the use of AI transform agricultural practices in Asia by 2035?

- What are the likely impacts on climate action in the region?

Scenario 1: Fractured Futures

Depletion of groundwater and climate-induced famine make it increasingly unviable for smallholder farmers to continue farming. Rising temperatures in the region are also making it harder for farmers to work long hours.

As food security declines, small farmers are taken over by agro-technology companies and consolidated into larger farm parcels. This also paves the way for the use of smart automation and AI in agriculture. Most farmers lose access to their land and work as contract labour.

The use of AI for improving crop yield improves agricultural productivity for a few years. Crop diversity however drastically reduces, and this contributes to a decline in the nutritional quality of food. The patenting of seeds by agro-technology companies and the steady erosion of traditional knowledge also compromise food sovereignty for most communities in the region.

As health problems increased globally, leading industrialised nations developed artificial biomes using advanced technologies to support agricultural production. However, this high-quality food remains out of reach for most.

Advances in AI for processing hyperspectral imaging have improved calculations of carbon sequestration and many companies offer AI-based tools to optimise agricultural practices accordingly. However, it remains unclear how long soil and forests can store carbon. Some organisations are concerned that a single-minded focus on sequestering carbon in soil and forests is contributing to greenwashing and could result in a loss of biodiversity.

The pretence of addressing the climate crisis through such mitigation measures combined with the loss of local knowledge systems drastically worsens the climate crisis in Asia.

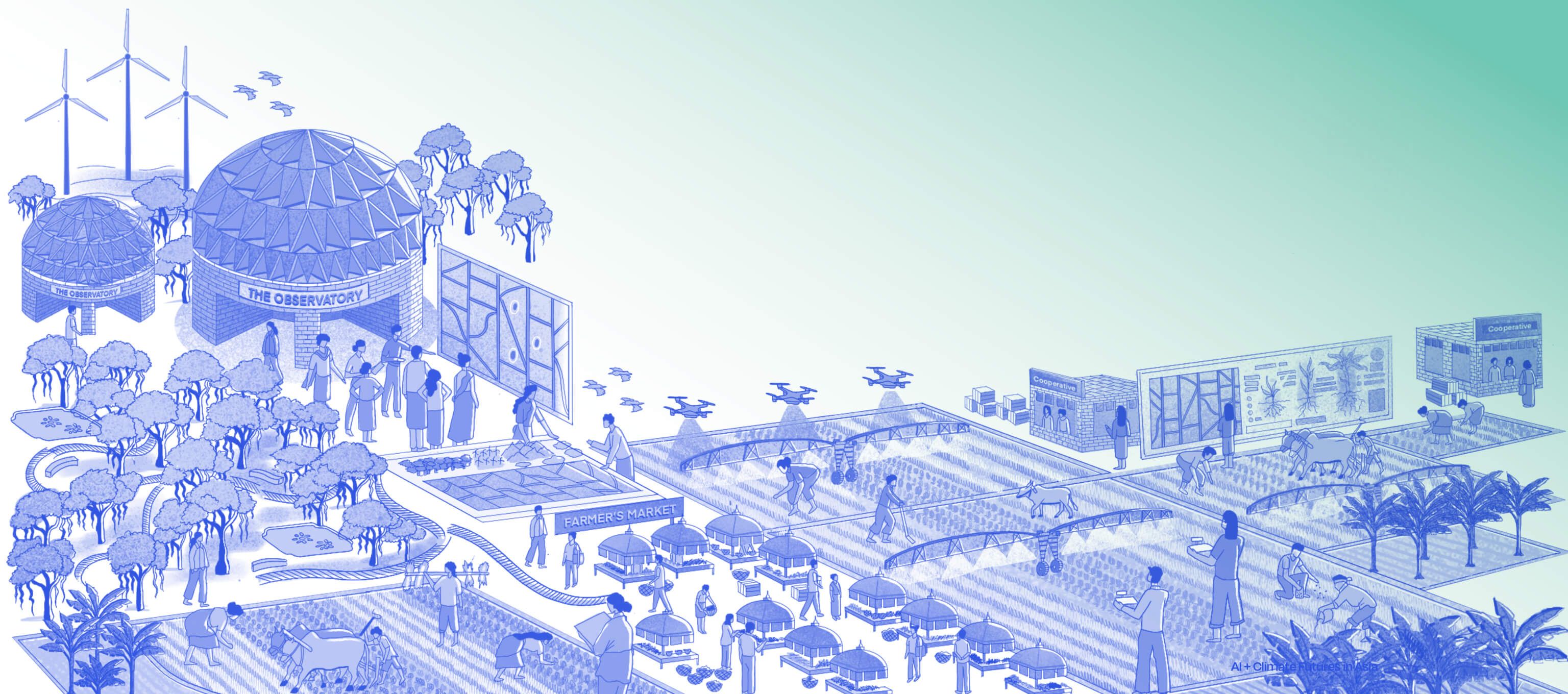

Scenario 2: Hopeful Tomorrows

Improvements in the quality of satellite imagery and coverage of remote-sensing equipment have drastically enhanced the quality of agricultural data in the region. Years of mismanagement and misuse of agricultural data by private companies had led to a breakdown in agricultural supply chains and a loss in public trust. Agricultural data is now managed by local academic and research institutes, many of whom have used this data to build digital twins of local agro-climatic zones. The quality of farm advisories has improved considerably, and farmers are better prepared to adapt to climate variability.

The growing recognition that smaller data sets and models, that address specific localised issues, are more effective for improving agricultural productivity has led to increased investments in community innovation hubs across the region. These hubs work to advance participatory models for problem identification and technology design. New applications that cater specifically to the needs and capacities of smallholder farmers and support traditional farming practices are being developed.

Off-the-shelf commercial applications are also available - extensive documentation around these products' features, capacities, and limitations, along with comprehensive customer support services, have helped these tools gain popularity.

These tools are also certified by a new regional institute - the Observatory for AI in Agriculture which monitors and evaluates the impact of emerging applications on ecological farming.

The shift toward more ecological farming practices, improvement in farming incomes, checks on greenwashing by companies, and a more judicious approach to AI development help stall the climate crisis in Asia.

These two scenarios on the future of AI and agriculture in Asia reflect a set of shared concerns voiced by the expert network and potential levers of change.

- Loss of agency, rights and livelihoods

- Inaccurate problem diagnosis

- Crowding out of traditional knowledge systems

- Commercialisation of Farm Data

- Declining Health and Environmental Outcomes

Shared Concerns

- Consultative Technology Development

- Trustworthy Data Institutions

- Monitoring and Evaluation

- Capacity Strenghtening

- Public Policy for Responsible Innovation